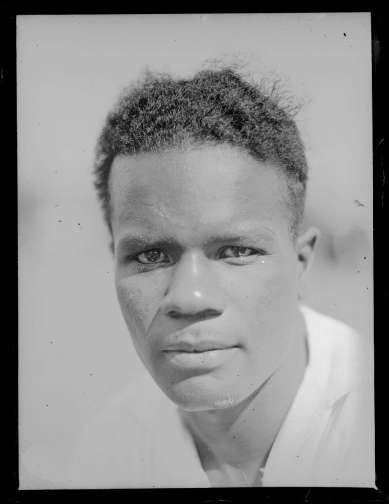

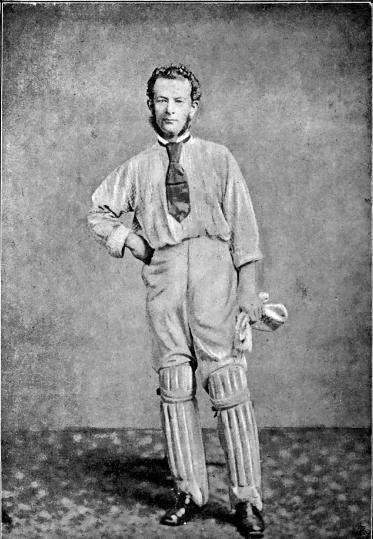

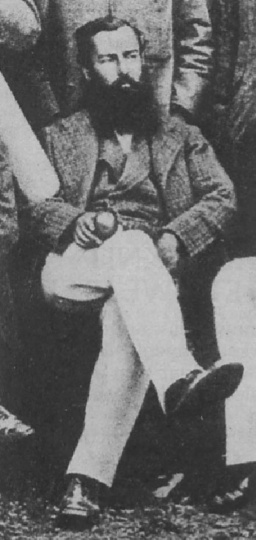

Fuller Pilch (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

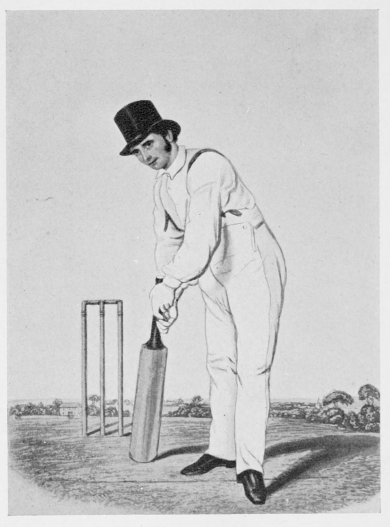

In discussions of who might have been the greatest or most influential cricketers of all time, there is a tendency to favour more recent players. Most critics understandably nominate those who they have seen in person, although an exception is usually made for the inevitable Don Bradman, whose statistical dominance makes him a special case. Perhaps one or two players from earlier periods, for whom there is plenty of film available (preferably on Youtube), might warrant a mention but once discussion moves further back than living memory, former stars are usually neglected, usually accompanied by assertions that cricketers from so long ago cannot possibly have been as good as their modern counterparts. This phenomenon is intensified by the lack of statistical detail available for comparison, and a suspicion that — depending on the viewpoint of whoever is judging — it must have been easier to score runs or take wickets back in the dim and distant past. One or two aficionados might buck the trend and name older players such as Walter Hammond, Jack Hobbs or Victor Trumper, but for most cricket followers these are at best just names that they have heard. And then there is the case of someone like Ranjitsinhji, recorded by the history books as the inventor of the leg-glance (but who is perhaps even more interesting for his adventures off the field). Or what about W. G. Grace? To those familiar with cricket history, he might stand comparison with Bradman: the man who invented modern batting, combining forward play, back play, attack and defence. But if we go back even further, cricket was a very different game on (and off) the field, so that any hope of statistical comparison breaks down hopelessly. Which is unfortunate because if we continue backwards, we come across names that were legends for a century after their playing days were over.

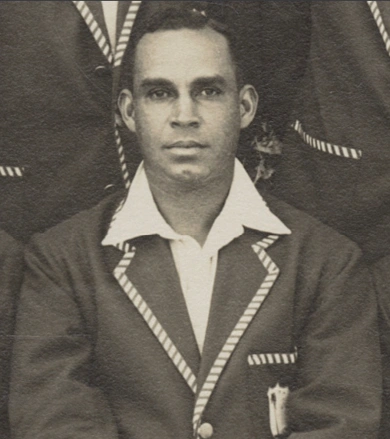

Standing at the head of this semi-legendary list was Fuller Pilch, perhaps the most famous batter before the emergence of W. G. Grace. During his playing days, there was a general consensus that Pilch was the best batter in England — and therefore the world. While never achieving the statistical dominance of those who followed — for example Grace, Ranjitsinhji, Hobbs, Hammond — any impartial assessment has to place Pilch among those names because of what he achieved at a time when batting was often little more than a lottery. When Grace emerged, it was with Pilch that he was most often compared in trying to decide who was the greatest; and not everyone agreed that Grace was better than Pilch. And across the vast span of time between the end of Pilch’s career in 1854 and the modern day, one of his batting innovations has survived and continues to be one of the foundations of the game.

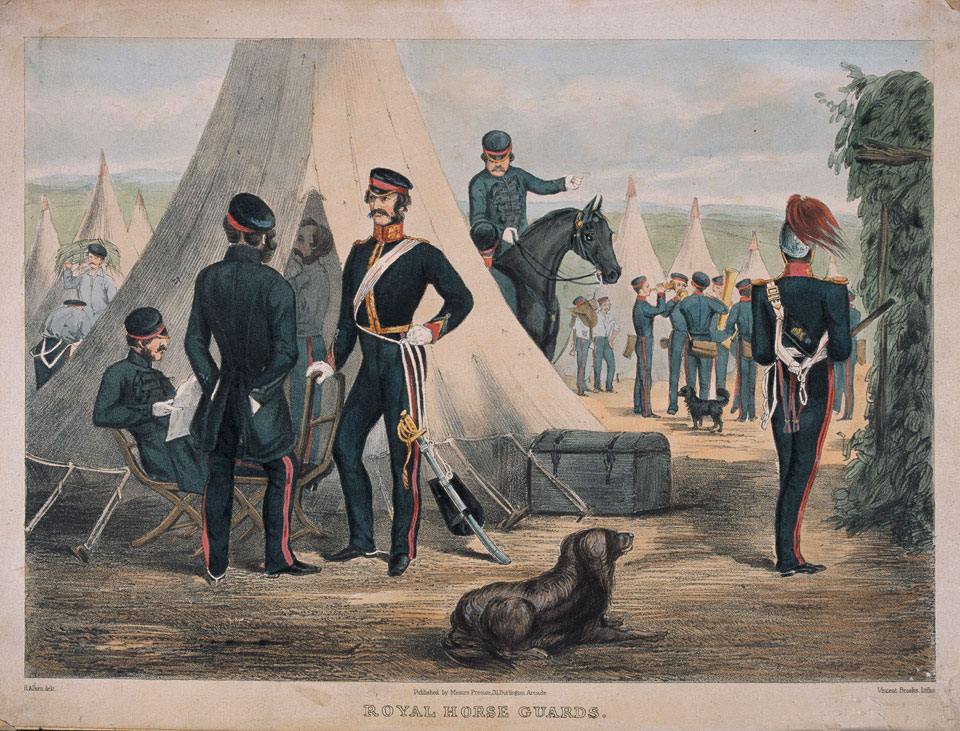

Before delving too deeply into Pilch’s story, it is worth establishing how very different cricket was when he was at his peak in the 1830s and 1840s. Cricket was played irregularly and few county teams even existed; there were no competitions or cups or championships and fixtures were arranged on an ad hoc basis with no real central authority to coordinate them. Test cricket was years away. Many games were played, especially at the major venues such as Lord’s, between what were little more than scratch teams. Part of the problem was that, at a time before the railway network had become fully established, transporting teams across the country was simply uneconomical. Single-wicket matches were still extremely popular, and followed closely by the press and public. While there were amateur and professional cricketers (Pilch was a professional), the distinction was less pronounced than it became; later generations of amateurs were more eager to keep professionals in their place, but in Pilch’s time the relationship was more benevolent. He described it: “Gentlemen were gentlemen, and players much in the same position as a nobleman and his head keeper maybe.” And the concept of what today would be called first-class cricket was largely unknown, although there was a sense that some matches were more important than others.

On the field, it was a similarly different game. When Pilch first played at Lord’s in 1820, the only legal form of bowling was underarm. Although “round-arm” bowling — in which the ball could be released from shoulder height — was widely used and became very effective, it was not officially permitted until 1835. Few, if any, batters used pads or gloves and on the field, long-stop was an essential position. The science of tending to pitches was almost unknown, and therefore the wickets were rough and untamed: the ball bounced unevenly (shooters were common) and could rise sharply if it struck the stones which were found in many playing surfaces. For bowlers who spun the ball, there was a huge amount of help from the pitch. Furthermore, games were generally played without a boundary — all hits were run out, with no fours or sixes. There might have been exceptions; during Pilch’s benefit match in 1839, wagons were used to enclose the ground, but we do not know if hits beyond this point counted as extra runs. But according to Rowland Bowen, one of the contemporary criticisms of W. G. Grace was that “Pilch played cricket, W. G. plays boundary”. In these circumstances, run-scoring was incredibly challenging; reaching double figures was an achievement and scores of 20 were perhaps as valuable as a century in modern cricket. And the development of round-arm (which gradually metamorphosed into over-arm) bowling was even more of a challenge; the big scores that had begun to accumulate before 1820 against simply lob-bowling disappeared and did not reappear until the time of Grace. Cricket had become a low-scoring game, and the surviving statistics reflect this. Those who later championed the claims of Pilch as one of the best ever were quick to remind audiences how difficult it was to score back in the 1830s and 1840s.

This, therefore, was the cricket world into which Pilch emerged and established himself as the best; alongside Nicholas Felix and Alfred Mynn, he became one of the few household names who played the sport. How did he reach that peak?

Fuller Pilch was born on 17th March 1804, at Horningtoft in Norfolk. He was the seventh (not the youngest as has often been claimed) child of Nathaniel Pilch (a tailor) and Frances Fuller (who was the widowed Nathaniel’s second wife). Records are scarce from so long ago — individuals were not recorded on the census until Pilch was 37 — and so there is much that we do not know. But Pilch’s later fame meant that some details were recorded; he and his two older brothers (the only three out of Nathaniel and Frances’ five sons to survive until adulthood) William and Nathanial followed their father’s trade, becoming tailors. However all three proved to be good cricketers as well. There are suggestions — based on one questionable newspaper report — that Pilch spent time working in Sheffield as a young man, and learned cricket there, but it is perhaps more likely that he played village cricket in Norfolk.

There are more plausible claims that Pilch was coached by William Fennex, one of the Hambledon stars from the period in the late eighteenth century when cricket’s popularity first exploded, and one of the first men to use what would today be known as forward play; Fennex himself claimed to have taught Pilch how to bat. The author Frederick Gale wrote in 1883: “Fennex, be it remembered that he inaugurated the free forward play, and taught it to Fuller Pilch, and Fuller Pilch taught the world; for I feel confident, in my own mind, that all the fine forward play which one sees now sometimes, is simply the reflex of what Fuller Pilch developed in a manner which has never been surpassed by any living man (except W. G. [Grace]), and that, too, in days when grounds were less true, and pads and gloves were unknown. And I say of my friend W. G., that he has simply perfected the art which Pilch taught, though Pilch was never such an all-round man as our present champion.” We shall return to Pilch’s pioneering forward play later.

As Pilch improved as a cricketer, he was selected to play for Norfolk — in reality at that time little more than the Holt Cricket Club — and he made his debut in “big cricket” when he played for Norfolk against the MCC at Lord’s in 1820. Pilch was just seventeen at the time, and played alongside his brothers Nathaniel and Francis. But the three fielded while William Ward scored 278 runs, the highest innings in what would today be called first-class cricket until W. G. Grace scored 344 in 1876. Pilch, at that time picked as much for his under-arm bowling as his batting, scored 0 and 2 as the MCC won by 417 runs. But for modern statisticians, this was his first-class debut, even though no-one would have had any notion of what that meant at the time.

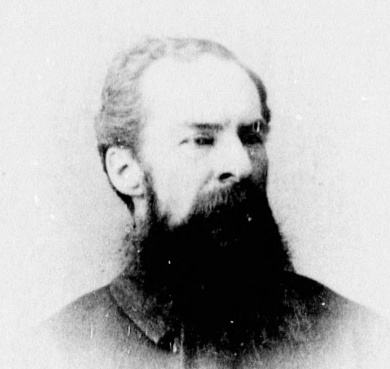

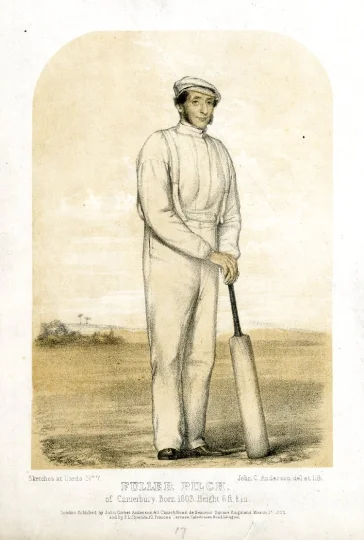

Fuller Pilch in 1852 (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The irregular and disorganised nature of cricket at this time mean that it is hard to track Pilch’s career in terms of statistical achievements. But he gradually became a more accomplished batter even though he did not play anything else recognised today as “first-class” until 1827. In 1823, he moved to Bury St Edmonds, and from 1825 to 1828, he played as a professional for Bury Cricket Club — his first century was scored for the club against Woodbridge in 1830 — and represented Suffolk. In this period he made some substantial scores and was selected for the Gentlemen v Players match for the first time in 1827. That year, he also played for a team styled “England” against Sussex in a series of three matches intended as a trial of the fairness of the new style of “round-arm” bowling (used by Sussex in those matches) and top-scored in the first game with 38. He did not stand out in the other games and, with several other “England” players threatened to pull out of the final game unless the Sussex bowlers reverted to underarm, before ultimately agreeing to play. But Pilch quickly learned to face the new style of bowling, adopted it himself, and when asked in later years about what it was like facing the old underarm style, replied: “Gentlemen, I think you might put me in on Monday morning and get me out by Saturday night”.

Pilch moved to Norwich in 1829, becoming the landlord of the Anchor of Hope Inn, and began to play for Norfolk, which was established on a more formal basis in 1827. Within a few years, it was one of the strongest teams in England, not least owing to Pilch’s batting. And in 1833, he became famous through two single-wicket matches against Tom Marsden, the “Champion” of England. Single-wicket was a highly popular form of the game at the time and was played under various rule. The main versions involved two players opposing each other without assistance in the field. Hits behind the wicket did not count, and batters had to run to the other end of the pitch and back to score a single run. Pilch comfortably won the two matches: in the first, played at Norwich, he won after dismissing Marsden for seven, hitting 73 runs himself and then bowling Marsden seventh ball for a duck, winning by an innings. In the return match at Sheffield, before 12,000 spectators, Pilch scored 78, to which Marsden could only reply with 25. Pilch hit 102 and facing an impossible task, Marsden was dismissed for 31. Just over ten years later, William Denison said of this game: “Pilch’s batting was of the finest description, and a better display of the art of cricket was never witnessed in any former match.” The contest was a huge attraction and received a great deal of press coverage. But for all his success, Pilch disliked single wicket matches and rarely took part: he turned down several opportunities (he and Alfred Mynn seem to have actively avoided facing each other in that format) and only seems to have played one other game (in 1845).

In other cricket, Pilch’s fame grew and there were hardly any big matches in which he did not feature. He played for Cambridge Town, “England”, the MCC, Norfolk, the Players, Suffolk and Surrey, and as a given man for the Gentlemen. He also featured in several of the “novelty” teams which were popular at the time, such as for the Single against the Married or the Right-handed against Left-handed. Perhaps his greatest year came in 1834. In two games for Norfolk against Yorkshire, he scored 87 not out, and 73 and 153 not out; he also scored 105 not out for England against Sussex and 60 for the Players against the Gentlemen. According to Gerald Howat (in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography), “his aggregate of 811 runs in major matches was not surpassed for twenty-seven years.” Such considerations were meaningless in 1834 — batting averages were not widely published, if at all — but his average of 43 in those games dwarfed the next best, which was only 18. And in matches retrospectively reckoned first-class, he scored 551 runs at 61.22. But perhaps more importantly he had reached three figures in “major matches” for the first time, in a period when such feats were a rarity.

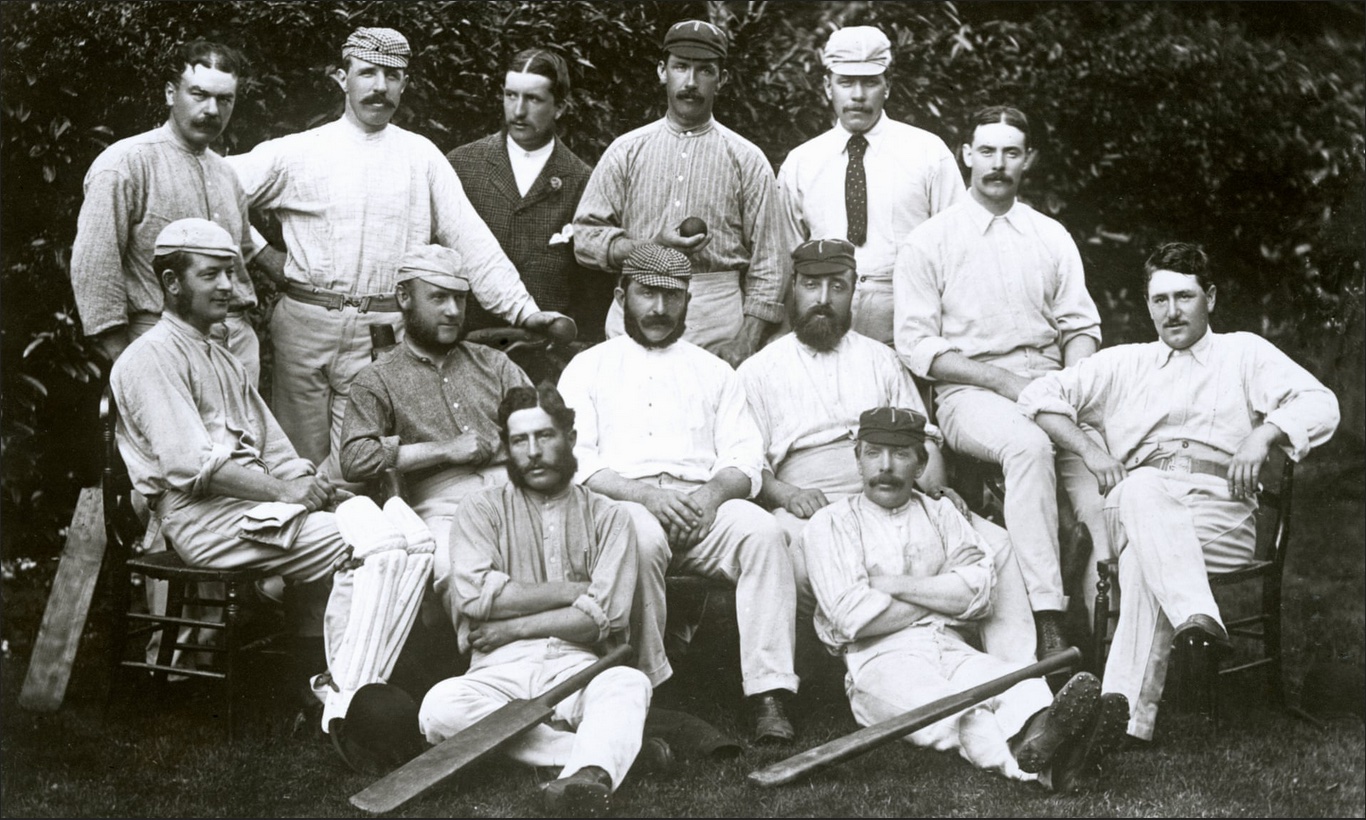

By then probably the best batter in the world, Pilch was in considerable demand and Norfolk could not hold on to him. A Kent county team — the second such attempt — was founded in Town Malling by a pair of lawyers called Thomas Selby and Silas Norton. After the 1835 season, they persuaded Pilch to move to Town Malling in return for £100 per year, for which he would play for Kent and manage the cricket ground. He made his Kent debut in 1836 and remained with the county until 1854, during which period he was a key figure in making it the strongest team in England. Perhaps its most powerful opposition came from another of Pilch’s teams: William Clarke’s professional touring side, the All-England Eleven. Clarke’s team made a huge impact on English cricket, and Pilch was a founding member, playing for the Eleven from 1846 until 1852. He played at least 65 matches for the Clarke’s Eleven, usually in games played “against the odds” (i.e. against teams featuring more than eleven players, to make the game competitive), and scored four half-centuries. But Pilch was not limited to playing for these teams. At a time when county cricket was an unregulated free-for-all, Pilch also made appearances for Hampshire, Surrey and Sussex. He was also a dominant figure in club cricket; he named his innings of 160 for Town Malling against Reigate in 1837 as one of his best.

A scorecard showing Pilch’s innings of 60 for All-England against Nottingham in 1842

While Pilch was an undoubted success on the pitch — for example, he was the Kent’s leading scorer in twelve out of nineteen seasons — he did not play regularly because Kent, like all county teams in this period, only rarely took the field. And his statistical achievements have been utterly dwarfed by the inflation in scores that took place in the later part of the nineteenth century; to a modern audience, his average looks poor but at the time, given the challenges of batting, it was a different story. His record surpassed that of any of his contemporaries. He scored eleven fifties for Kent in 84 matches today reckoned first-class, with a highest score of 98, and his average of 19.61 was very good for the time. Of these matches, 36 were played against a team styled as England, which contained many of the best players: in these games, he scored four fifties and averaged 18.15. And in the Gentlemen v Players match, which was the highest form of representative cricket in England in the days before Test matches, he played 23 matches — 21 for the Players (the professional team) and two as a “given man” for the Gentlemen (the amateur team) to make the match more competitive — and averaged 14.90. As a point of contrast, he was easily the dominant batter for Kent in this period. Of his contemporaries to score 1,000 runs for the county, none approached his average: Tom Adams had 2,291 runs at 12.58; Nicholas Felix scored 1,528 runs at 16.79; and Ned Wenman had 1,063 runs at 10.42.

Hidden among the fragmented and hard-to-process figures, Pilch was remarkably consistent. It was a matter of some note that in 1836, he reached double figures in 13 innings (five of which surpassed 20); and in 1841 he reached double figures 16 times (not all of which are today judged as first-class) within which were two scores in the 20s, two in the 30s, three in the 40s and one in the 60s. In his Sketches of the Players (1844), William Denison listed many of these achievements, and wrote of Pilch: “But there are other seasons wherein Pilch has outshone all his competitors, and were they to be enumerated, it would be be to extend this publication to a size far beyond that of a ‘sketch’.” He also stated: “As a bat, [Pilch] has been one of the brightest luminaries of the cricket world, during the last 20 years.” In short, there was little doubt of Pilch’s class and superiority; he was quite simply the best batter who had played until then.

This was a precarious time for county clubs and several teams flitted in and out of existence. Kent was no exception: the Town Malling incarnation of the club struggled financially and collapsed in 1841. But Pilch maintained his Kent contention. When the brothers John and William Baker, the founders of the Beverley Club at Canterbury, took over the organisation of Kent teams in 1842 (when their club effectively assumed the role of the county team), they appointed Pilch as the manager of the Beverley Ground. When the proto-Kent team moved to the St Lawrence Ground in 1847, Pilch again moved with them, taking charge of that ground too. There are a few other traces of his life around this time. Despite claims by Denison, there is little evidence that Pilch ran a public house in Town Malling. Instead, he seems to have worked as a tailor in cricket’s off-season; this was the occupation recorded on the 1841 census (which was taken when he and the Kent team were staying at The Bear in Lewes, during a match against Sussex).

For all of Pilch’s later claims — such as the Kent team being a “eleven brothers’, or that “as soon as a man had been 12 months among the cherry orchards, hop gardens and pretty girls, he could not help becoming Kentish to the backbone” — his loyalty to Kent perhaps owed more to finance than emotion. After being awarded a benefit match — the lucrative Kent v England game in 1839 — he accepted an offer (“too good to refuse”) from Sussex to move county; it required the intervention of some of Kent’s wealthier patrons to persuade Pilch to remain where he was.

Pilch played on until 1855, when he was 52 — he later admitted that he and several of his team-mates kept going too long, meaning that Kent declined in the 1850s — having spent 35 years playing at what then was the top level. In terms of what is today judged as first-class games, Pilch scored 7,147 runs at 18.61, including three centuries and 24 fifties. He also took 142 wickets (although analyses do not survive for most of these). But it was noted at the time that he had scored ten centuries in total, a remarkable number for the time; he was also reckoned to have appeared 103 times at Lord’s.

The Saracen’s Head in Canterbury, photographed around 1945; the building was demolished in 1969 (Image: Dover Kent Archives)

Pilch continued to play minor cricket for one more season, appearing for the Beverley Club in Canterbury, and then from 1856 until 1866 concentrated on umpiring: in this period, he stood in 28 matches today reckoned first-class, almost all of which were played in Canterbury. He also had other cricketing interests. He began to work as a bat manufacturer — his occupation as given on the 1851 census — and continued as what would today be termed the head groundsman of the St Lawrence Ground until 1867. This was not the only ground with which he was associated. In 1849–50, he went into partnership with Edward Martin, another Kent cricketer, and developed the Prince of Wales Ground in Oxford, where he undertook winter coaching. This business partnership ended in 1855, at which point Pilch began another partnership with his nephew William Pilch, in whose house he was living in 1851. The pair became joint licensees of a Canterbury public house called the Saracen’s Head. It is not quite clear how the responsibility was split: the proprietors were often given as “F. and W. Pilch”, but William was sometimes named alone, and was listed as the head of the household on the 1861 census. From the little evidence that survives, William looks to have been the primary licensee. For example, on the 1861 census when Pilch was living at the Saracen’s Head with his nephew, William was listed as an innkeeper employing three male and three female servants; Pilch by contrast gave his occupation as a cricketer.

This particular business scheme was destined to end badly. William continued to run the Saracen’s Head for most of the 1860s but drifted into growing financial strife. Part of the problem was the new railway station that had been built in Canterbury; whereas the Pilches had previously enjoyed the custom of people (such as farmers) who would stay overnight in their establishment, the growth of the railways made this unnecessary as journeys could be made more quickly with no need for overnight accommodation. As a result, the Saracen’s Head lost valuable business. But there was also something of a financial crisis at the time that affected many small businesses after a leading bank in London collapsed. It was probably a combination of these factors that led to William’s ruin: in 1868 he was imprisoned for debt and declared bankrupt the following year, owing his creditors almost £700. By then, Pilch’s health was bad and he had been forced to give up his work as groundsman. His friends seemed to think that the problems over money with the Saracen’s Head had a negative effect on him; more than one report stated that it had been Pilch himself who had been declared bankrupt. Frederick Gale for example wrote in The Game of Cricket (1888): “The last time I saw Fuller Pilch was a few months before his bankruptcy, which, I believe, killed him. The world did not prosper with him as it ought, and he was out of spirits, and got so excited about the old times that I had to drop the subject.”

Pilch’s failing health — he was suffering from rheumatism — forced him to give up work and money became a struggle, especially with the problems faced by his nephew. Some Kent supporters arranged a subscription which it was hoped would provide him with a pension, but it fell short of expectations; some wealthy patrons had to top up the fund to provide him with an income of one pound per week. In April 1870, Pilch’s health took a turn for the worse. On 1 May 1870, he died at William’s home on Lower Bridge Street in Canterbury from what was then known as dropsy but would today be called fluid retention (or oedema); the actual cause was perhaps most likely to be heart failure. As a mark of the respect in which Pilch was held, a collection was taken among the public, the proceeds of which were used for a memorial. An obelisk was placed over his grave at St Gregory’s Church, which was moved to the St Lawrence ground in 1978 after the church had fallen into disuse. In 2008, Pilch returned to the news when plans by Christ Church University to redevelop the site of St Gregory’s were paused after it became clear that no-one was sure where Pilch was buried. An old photograph of the memorial eventually cleared up the mystery, and work went ahead; a new headstone was placed to mark the approximate location of Pilch’s grave.

The original memorial to Pilch in St Gregory’s churchyard, Canterbury, in the 1950s (Image: Kent Online)

So much for the facts. It is perhaps not as complete a story as we would like, nor could it ever be as detailed as a biography of Grace or Ranjitsinhji or Hobbs because it was plainly a very different world for cricketers of Pilch’s time. It is not possible to simply go through each season and note his scores in the biggest games or reel off impressive aggregates and averages. And yet there was no doubt among Pilch’s contemporaries that he was the best of all. As it happens, it is possible to get a glimpse of what might have made Pilch so good. But that is not the only way in which his legend continued. His reputation endured so that when W. G. Grace came along, Pilch was still for many the point of comparison. For some who remembered him, Pilch’s success must have been more meretricious simply because batting was more difficult back then. And so, more than 30 years after his death and over half a century since he last took to a cricket field, Pilch’s name became embroiled in a debate that has never been settled: was cricket a sport that continually improved, or one that was in a permanent state of decline? Were those who played in the past better than those seen in contemporary cricket? Or were the current players the best of all time?